Introduction To Poetry

I first ran into Billy Collins before I even thought I would get anywhere near poetry. I ran smack into his poem “Introduction to Poetry,” to see him “walk inside the poem’s room / and feel the walls for a light switch.” I saw him “waterski / across the surface of a poem” and “press an ear against its hive.” Then I got to the end and watched as his students “tie[d] the poem to a chair with rope / and torture a confession out of it.” If you haven’t read “Introduction to Poetry” by Billy Collins, once you do, you will never analyze a poem the same way. It’s because poems are meant to breathe, they are meant to reside in the silences of the crevice of book, of the mind. Not to be shredded into an English paper.

Poems make me happy. They do. If there was anything I wished for anyone in this world, it would be to feel the happiness I felt when I read “I’m nobody! Who are you?” by Emily Dickinson, or the first time I came across “Trees” by Philip Larkin, or the beautiful “Musee des Beaux Arts” by W.H. Auden. Poetry isn’t about the poets or belonging to some elite club of poets—a common misconception—it’s about the poems. It’s about the everyday belongingness, inclusiveness, when you read a poem about humanity. Because all poems are about humanity.

And who more to talk about the life of poetry than the former US laureate and New York State laureate Billy Collins. Even with the above-mentioned poem, “Introduction to Poetry,” and throughout all of his poetry, you can tell he wants to connect with his audience. He isn’t dumbing down poetry, not at all, but he is creating the 21st Century Lyric, one about the daily activities of people. The quiet moments of rapture when we press our ears to the grass, or the memory of childhood in the sight of mouse—all of these become moments of beauty in his poetry.

The very first poem in Billy Collins’ horoscopes for the dead tackles silence. This is something I’ve always wondered about—how to achieve silence in a world so busy with yack, yack, yack. As I write this now at a café, a waitress is serving busy clienteles, and the song overhead is loud and boisterous. Yet, as I read “Grave”:

…Then I rolled over and pressed

my other ear to the ground,

the ear my father likes to speak into,

but he would say nothing

and I could not find a silence

among the 100 Chinese silences

that would fit the one he created

even though I was the one

who just made up the business

of the 100 Chinese silences—

the Silence of the Night Boat

and the Silence of the Lotus,

cousin to the Silence of the Temple Bell

only deeper and softer, like petals, at its farthest edge.

I cannot help but feel his silence…about his father, about the power of contemplation, about the power of the imagination that make up silences, about the beauty of the petals. And so ends his first poem that draws me into horoscopes for the dead.

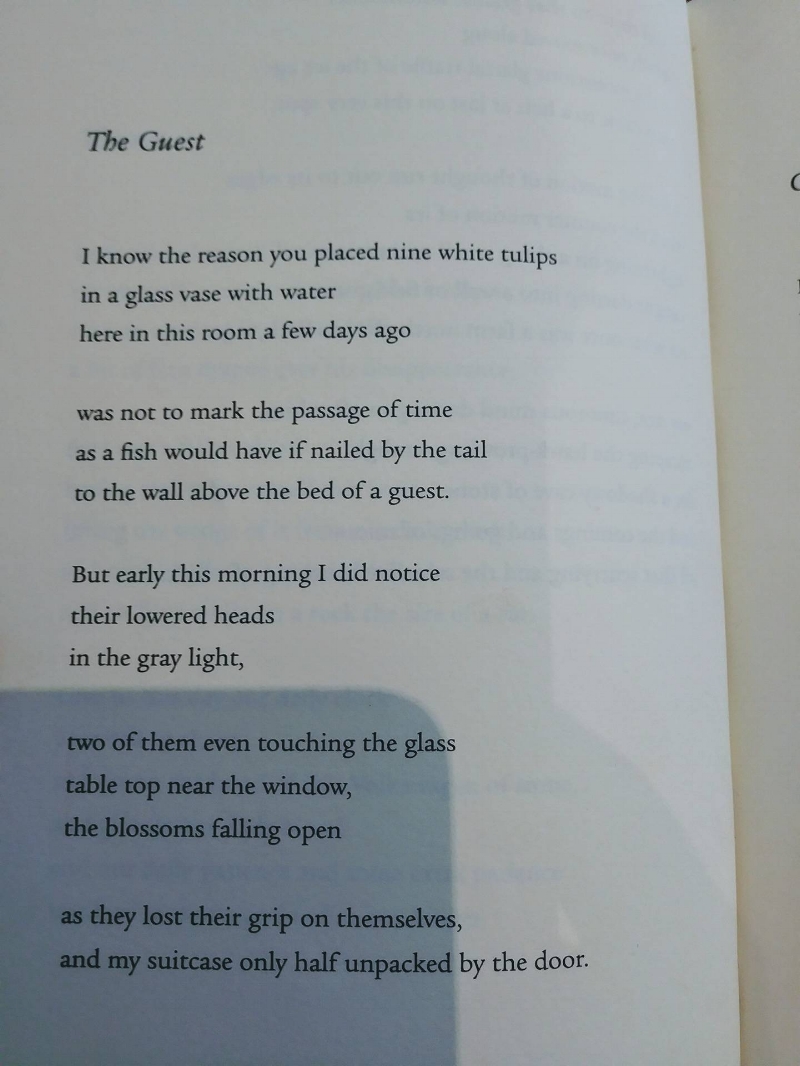

Now for a poetry lesson—I love form, because form resides everywhere. A building is held up by the formation of its foundation. A car by its hood. A shirt by its sleeves. Form is everywhere. Some of the stuff I learned in my fancy schooling about poetic form is that its practically invisible, but if you take a moment to notice, you can see how well the poet builds the poem through its form. The most popular form that the poem takes (if it wants to, because you never know where the poem is going to go) is what we call the sonnet. Now, there are a million different forms a sonnet takes, but there are two typical sonnets, the Italian and the English. The English sonnet, as popularized by Shakespeare in 154 sonnets, is the fourteen-line sonnet. Although Billy Collins’ “The Guest” has abandoned the rhyme scheme, I can spot the form of a sonnet, the beginning observation, the turn in the middle, and the ending with the ironic couplet. It’s a small story, the sonnet, and here, we don’t realize who the guest is until the ending. Marvelous. Here is the complete poem:

This is the poet that loves to talk about poetry, and while we are talking about poetry, let’s tackle Billy Collins’ “Memorizing ‘The Sun Rising’ by John Donne.” You don’t need to know anything about John Donne, but if you do, it helps, so here it is. It’s pretty self-explanatory, both poems. But in this one by Collins, the dramatic situation is of memorizing that poem by Donne, and the poem gliding like a “blown-out candle” from the mind. I love the part, though, when he says:

Then, after my circling,

better than the courteous dominion

of her being all states and him all princes,

better than love’s power to shrink

the wide world to the size of a bedchamber,

and better even than the compression

of all that into the rooms of these three stanzas

is how, after hours of stepping up and down the poem

testing the plank of every line,

it goes with me now, contracted into a little spot within.

I hope I leave you with a little Billy Collins in the pocket of your mind. I hope you enjoyed the poetry. I hope it wasn’t a boring lesson, but a testament to what centuries of writers have loved, little compressed stanzas. And amidst all the busyness of life, I hope you sunk your feet in and enjoyed what little silence this article brought.

Angela Gabrielle Fabunan, 28, is a resident of both New York City and Olongapo City. She has been published in Eastlit Journal, Cha Literary Journal, the Philippine Daily Inquirer and Maganda Magazine. In 2016, she won Third Prize in Poetry at the Don Carlos Palanca Memorial Awards. In 2017, she won Honorable Mention in Poetry at the Amelia Lapena Bonifacio Literary Awards. She graduated with a BA in English from Bowdoin College and attended grad school at the University of the Philippines. She is an avid fan of pop music, a dog-lover, and a tea-drinker. Aside from writing poetry, her goal in life is to find the best jalapeno chips in the world. She has yet to find them, but is open to suggestions.

Email: agtfabunan@gmail.com

Facebook: Angela Gabrielle Fabunan

Instragram: @poetrymemory

“If you haven’t read ‘Introduction to Poetry’ by Billy Collins, once you do, you will never analyze a poem the same way. It’s because poems are meant to breathe, they are meant to reside in the silences of the crevice of book, of the mind. Not to be shredded into an English paper.”